Photo by Shane Rounce on Unsplash

Introduction

Teacher/student motivation and engagement is at the forefront of what we are trying to ameliorate at Fort St. James Secondary School. The new curriculum, as of 2016, gives us the freedom to fully explore cross curricular and inquiry methodologies in our school. Beyond that, our close-knit educational environment of 280 students and 20 teaching staff, allows us, as teachers, to work together to utilize a cross-curricular framework, to guide our students in breaking free from the traditional classroom model, and engage them in the learning of their own choosing. Throughout this Master’s Degree we plan to focus on three predominant areas of study: Social Studies, Digital Media, and Carpentry. As a general query to guide us in this process, we are asking the question, what are the benefits, for both teachers and students, of employing Cross-Curricular Inquiry on student motivation and engagement, at Fort St. James Secondary School? Furthermore, we are hoping to hone our skills as practitioners of collaborative inquiry, to enhance the emerging atmosphere of the facilitation of effective, and differentiated student learning.

Paper Overview: A method for teacher inquiry in cross-curricular projects: Lessons from a case study by Katerina Avramides, Jade Hunter, Martin Oliver, and Rosemary Luckin

Prior to adopting an inquiry model for our students to adhere to, it is prudent that we, as educators, believe in the efficacy of the inquiry model, as a process. Indeed, “teacher inquiry offers a powerful, participatory, and evidence-based approach to innovation in schools” (Avramides, Hunter, Oliver, & Luckin, 2014, p. 259). A method for teacher inquiry in cross-curricular projects: Lessons from a case study, examines the benefits of a cross-curricular STEM project in a highschool. Avramides K. et. al., discuss their results including: teachers’ use, and comfortability of using digital, tools to record and report on student data, how to include teacher involvement in cross curricular applications or projects, and support from top management levels in regards to implementing cross-curricular learning within a school.

Avramides K. et. al., report that inquiry must not be forced on teachers, but rather led by teachers. In order for cross-curricular inquiry learning to be a success, teachers need to be willing to “provide an environment that supports long-term change…[and be] initiators of change.” (Avramides, K. et. al., 2014, p. 249) This article resonated with us, as it illustrated how there can be challenges in implementing cross-curricular design, especially when teachers are not willing to collaborate in small teams, to assess and discuss issues that come up, while engaged in this style of learning. Often, they are not comfortable with specific digital tools that are used to log student performance. Specific outcomes from the case study, include: 1.) The necessity of collaborating, amongst the project lead and involved teachers, must be constant and take into consideration one’s knowledge of the digital platforms being implemented to record data. 2.) The type of research method(s) implemented may not be preferred by all. Some may prefer qualitative or quantitative methods, which may influence how data is collected and reported on. 3.) Interviews (qualitative research) with individual teachers on their experience of the inquiry process revealed, more than surveys did, because the teachers had the opportunity to discuss their specific challenges. 4.) Instructors’ use of digital tools to communicate their inquiry into student learning, varied on comfort level. 5.) There is a balance between teacher autonomy and controlling what or how the teacher-researcher conducts their inquiry. (Avramides K. et. al., 2014)

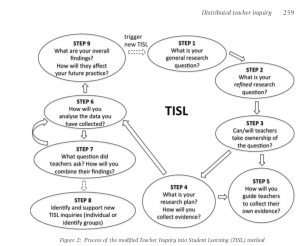

The above diagram represents steps educators can follow to implement their inquiry of student learning. It is also a similar model that students can employ to complete their own inquiry research. Furthermore, this model follows the similar cycle of questioning, reflecting, and producing, that the Action Research methodology employs.

Avramides K. et. al., reminds educators, and administrators, that using inquiry in a cross-curricular fashion is a learning process for all involved; it involves collaboration, and re-visitation, of the processes to facilitate students’ success. Furthermore, educators will require, “training and support to develop learning designs,” (Avramides K. et. al., 2014) that will enable educators to easily collect data, and support students, in their learning processes. Lastly, the challenges endured by staff, that were presented in this article, would be similar for students if they were to complete an inquiry on a particular project, or within disciplines. It takes time to gather information, record data, reflect, and process. Students, like the educators in the article, will need communication, feedback, and support.

Social Studies

Following the new curriculum for Social Studies, as set by the BC Ministry of Education, the goal for the Social Studies curriculum is to, “give students the knowledge, skills, and competencies to be active, informed citizens who are able to think critically, understand and explain the perspectives of others, make judgments, and communicate ideas effectively.” Four BIG IDEAS, or concepts, that learners focus on in Social Studies 10, include: “Global and regional conflicts shape our world and identities; Economic, social, geographic and ideological factors influence the development of political institutions; World views lead to different perspectives and ideas in the development of Canadian society; Historical and contemporary injustices challenge Canada’s identity as an inclusive and multicultural society.”

Students will be working on inquiry projects that involve two components. The first portion includes the learners’ use of their digital skills to highlight their question, document their learning experience, track progress, and explain the answer to their inquiry question. The second portion of the project involves, the creation of a culminating showpiece, or artifact, that learners’ believe represents an important segment of their research.

For their inquiry project, students can work either independently, or with a partner, and they will have the opportunity to choose a topic, that resonates with them, from within one of the four big ideas. Students will use a format of, “I need to know about…..” or, “I wonder about….” in order to assist them in developing their question, thus leading into their inquiry project. For example, a student may use the aforementioned format to assist them in developing their inquiry question: “I wonder how new technology impacted Canada’s role in WW2?”

During the inquiry process itself, students can choose a digital platform, including Prezi, blog, or power-point, with which to record their inquiry process. Here, students can document their specific inquiry steps, including: question development, list of resources, reflection and/or collaboration if working with a partner, on what they understand through the completion of their reading, what they found interesting, connections to the inquiry question, and their conclusion. This digital documentation illustrates the learners’ journey, much like a timeline or story-map, and it can serve as a reference which can be referred to throughout the inquiry process. This portion of the inquiry project can be developed in the computer lab, or the library.

The second portion of the inquiry process is the construction of the showpiece. Students will have the opportunity to design a 2-D or 3-D model, or a web-page, that represents a segment of their inquiry that they found particularly interesting to their learning. The item created can involve using the computer labs for web page design, video, 3-D printing, or constructing in the carpentry class (for example building a wooden diorama, or using the Computer Numerically Controlled Router – CNC machine). If using the 3-D printer or CNC machine, students can work in the computer lab to create and download their designs in order to print. Students using the CNC machine will have to ensure that the wood they are using is prepped, and ready, prior to commencing the engraving process. Similarly, if students are working to build a model in the carpentry shop, students again, will need to ensure that their wood is accessible and prepped as necessary.

Upon completion of this inquiry project, students will have the opportunity to present their work to the class. Students will use their digital diary to illustrate their learning process, and the outcome to their inquiry question. Students will also have the chance to showcase their 3-D model, 2-D model, or other media representation, and explain why it was important for them to construct their particular model, and its connection to their inquiry.

The purpose of the project, is to engage students, in developing questioning skills, research, and data collection skills, in an area that is interesting to them. At the same time, this relates it back to one of the four main ideas of the course. Furthermore, engaging students to digitally chart their learning process, enables them to visually see and understand, their progress (or meta-cognition) down the pathway of inquiry, or personal discovery. The creation of the showpiece incorporates skills learned from Digital Media Arts, and or Woods/Carpentry courses, to further provide students with the opportunity to promote their creative skills, knowledge, and kinesthetic learning.

Limiting factors of completing an inquiry project in this fashion include: time, and having staff that support, and believe in, the cross-curricular model. First, in terms of time, creating a detailed timeline with students, prior to beginning the process, enables them to have some say in what they feel is an acceptable amount of time, and also puts the responsibility on them, to adhere to the agreed upon plan. That being said, the project should not be allowed to drag on, and students should be prepared to have regular check-ins with the teacher. Second, it is essential to have staff that you can work with to create cross-curricular projects, support each other, and learners, in this developing process.

Digital Media

As an Applied Skills Department, we are working towards a more inquiry based platform of learning. We are looking into student-centered approaches of meeting the new curriculum. The big ideas are replacing the limiting prescribed learning outcomes. This is essential to making inquiry possible, as the students are more free in displaying, how they learn, what they learn, and route in which to learn it. In my classroom, the idea of stand and deliver does not go past grade 8, and even with the 8’s, I will teach a concept, and then their project is based on open criteria. My goal is to teach to passion, and not create automatons. The ideas of problem solving, working as a group, and grit, are all key to my room. This is a rapidly changing world, and I want to help prepare the students, so they can meet future changes with adaptability.

Digital Media is an emerging field that changes on a daily basis. The idea of media and technology is so vast, that to truly meet the students desires, and passions, one must be willing to have a diverse classroom. Furthermore, the needs of technology goes far beyond my classroom. At any one time, I can have as many as 15 different software programs being used, as chosen by the students. This is designed to engage all learners, in their passions. What is great about this, beyond the engagement in the room, is the applications that can be seen, and used, in other courses.

Technology, and cross-curricular applications, are growing substantially at Fort St. James Secondary School. At any time, the computer lab is filled with students from other disciplines, creating show-cases of their learning, using the technology provided in the lab. Though this creates a busy and dynamic place, as those students are adding to the learners that are already there for class, the diversification of the software use is what is truly amazing. Students from English class will be making videos, and editing them, about their inquiry projects. Students from French, will be in the lab, creating visual representations of French art, and culture. Social studies students, will be in there for research and inquiry based projects, or creating political cartoons etc. That is to say, the lab is always bustling, and the teacher is very busy, but that is the point. The more our school can utilize its labs, to engage learners, the more the actual learning is on the learner. Teachers as facilitators, is a growing idea in our school, and one that we are keen to promote.

The shop and the computer lab, share a lot of work, as we use the Computer Numerically Controlled (CNC) router to make: table tops, signs, and plaques for the students, school, and community. The board preparation and finishing, is done in the shop and art room, but the design happens in the computer lab. This is a great example of different disciplines working together to make this happen. The students flow between the rooms to get the work done. The thing that this method requires, is a willing group of teachers, who are flexible.

The shop, computers, textiles, and art teachers at our school, are always willing to have an extra body in their class, to help move a project forward. This agreement is fluid, in that there is no defined time, that we are doing a project “together”. The idea is that all the shops and labs, are open to the students during class time, to go and work on interdisciplinary projects. The de-segmentation of our classes, and the movement of our students, makes the school, the classroom.

Carpentry

Learning carpentry basics, not only teaches students how to create objects, but provides them with a set of practical skills, they will be able to use throughout their lives. At its core, students engage in a process that allows them to: familiarize themselves with the many tools they will likely use during adulthood, conduct minor repairs on their home or property, help them build spatial cognition, and provide them with an engaging avenue to pursue inquiry based projects. Furthermore, this maker space, lends itself as an open, accessible, and hands-on learning environment which is conducive to getting students moving, interacting, and creating.

The key tenets of Carpentry have been updated in 2016, and are laid out on the Government of British Columbia’s New Curriculum website. The main categories of learning now include: understanding context, defining, ideating, prototyping, testing, making, and sharing (“Woodwork 11,” n.d.). These categories set a reasonable, and practical, framework for students to engage in the inquiry process. Regardless of what project the students are pursuing, it is possible to meet each one of these criteria set for by the Government of British Columbia. If we look at a true cross-curricular model, it can be argued that a student is also able to achieve competency in this curriculum, while working on an inquiry project, for another course.

Take, for example, a student that is participating in Deirdre’s Social Studies class. This student becomes fascinated with, the Iliad and the Odyssey. After examining these works, the student wants to focus on the fall of Troy, specifically the use of the Trojan Horse. As part of their final sharing, they decide to build a working replica. After designing the blueprints for a replica of the Trojan Horse, in Andrew’s Digital Media class, they then have the option to use the three dimensional printer, or come to the carpentry shop to represent their learning. Ultimately, at this stage, the student will have already completed the context, defining, and ideating processes, as outlined by the Government of British Columbia. If they complete this project here, they will also effectively prototype, test, and make their project. Finally, by completing their sharing, in a show-case of their inquiry, they have met both the Social Studies and Carpentry curriculum, and should be credited as such.

This example, demonstrates the potential flow of students during a semester at Fort St. James Secondary School, with each student, or small groups of students, pursuing their areas of passion. Despite this success, there are a number of difficulties related to Inquiry learning that need to be addressed. The most dominant of these issues, is the limited shop space available, and the limited specialty staff, to manage students pursuing an inquiry with a carpentry component. With only a single carpentry teacher, the shop space is limited to twenty four students. We have made this limitation work, thus far, by relocating students not directly working on the building aspects of their project, to another space. For example, the planning, designing, and blueprinting components, can be done in the computer lab. Although this has worked well here, it may lend questions to scalability in another site.

Training students to use the potentially hazardous equipment, is also a difficulty in the inquiry process. As the inquiry model lends itself to the free flow of students, and allows for a broad time-frame in which students may arrive in the shop, it is challenging to ensure each student is receiving adequate machine training. Training itself, takes a number of direct hours of support from the instructor. It involves a paperwork component from the Ministry of Education and WorksafeBC, a demonstration component, as well as a practical component – which is repeated until proficiency is achieved. This is most efficiently done in groups, as it takes a considerable amount of the instructor’s time to complete. It is best to gather as many students early on to complete this component, but all too often students are missed, or express interest in carpentry at a later time. Ultimately, we support all of the students through this process, in our small school, but this again, speaks to the potential challenge of scale, using the inquiry process.

Conclusion

It is clear that an inquiry-based methodology is both a valid, and efficacious, form of learning, that encourages our students to not only seek meaning with what they are learning, but become engaged in a fulfilling conversation with it. As was clear in the article, “A method for teacher inquiry in cross-curricular projects: Lessons from a case study” (Avramides K. et. al., 2014) there are some issues when trying to present an inquiry-based system; the most important being both teacher buy-in, and teacher autonomy. The research shows that a top-down approach, though possible, is not the most effective, as it overrides the idea of autonomy. True inquiry, should be organic, and a place of comfort for the teachers. Furthermore, there needs to be a strong, and willing, small group of teachers that are going to work together to implement the best strategy. The article states that, “there is a fine balance to be struck between controlling what teachers do and maintaining cohesion” (Avramides K. et. al., 2014, Pg. 258).

Here at Fort St. James Secondary School, we have that small, willing group of teachers, trying to push the boundaries of student learning. What we are trying to create, is a culture of inquiry, that is both organic and fluid. The idea of learning, and representation of that learning, happens only in one class, is being challenged and re-structured. Our school, has many champions to the inquiry approach, and the administration is very supportive in challenging the status quo.

References

Avramides, K., Hunter, J., Oliver, M., & Luckin, R. (2014). A method for teacher inquiry in cross-curricular projects: Lessons from a case study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(2), 249-264. doi:10.1111/bjet.12233

McAteer, M. (2014). Getting to Grips with Perspectives and Models. Action Research in Education, 21-42. doi:10.4135/9781473913967

Social Studies. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/social-studies/core/introduction

Woodwork 11. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/adst/11/woodwork

Resource List

https://fsjss.sd91.bc.ca/Pages/default.aspx

https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/doi/epdf/10.1111/bjet.12233

http://sk.sagepub.com.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/books/action-research-in-education/n3.xml

https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/adst/11/woodwork

hhttps://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/social-studies/10/

ttps://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/social-studies/core/introduction

Recent Comments